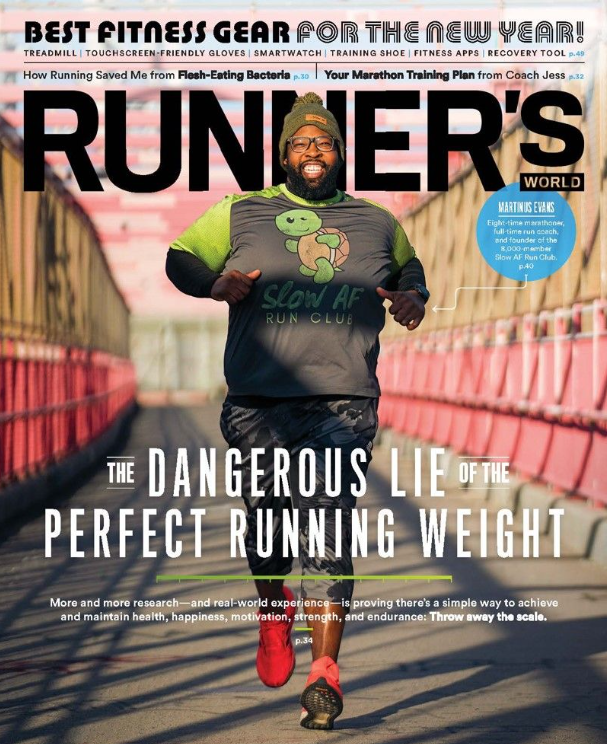

The Friendship Bench and the power of grandmother-led therapy

Image: The Friendship Bench

In 2005, a young Zimbabwean psychiatrist Dr. Dixon Chibanda, experienced the tragic loss of one of his patients. She had been desperately wanting to meet with the doctor following a failed suicide attempt, but could not afford the $15 bus ticket to travel to the capital city Harare from her home 100 miles away. Unable to receive the mental health care she needed, she sadly took her own life. Following this devastating and avoidable loss, Dr. Chibanda was determined to find a solution that would tackle the severe lack of access to mental health services in the country and beyond. With little funding and no new infrastructure to work with, Chibanda conceptualized the Friendship Bench and created a pathway to community-led healing and mental health care for thousands of people.

During that period, as one of just 12 psychiatrists in a country of over 16 million, Chibanda realized that he would need to get creative with his approach. His vision was simple — a bench placed in a safe community space, where anyone could have free access to one-on-one talk therapy. But with professionally trained mental health practitioners a scarce commodity, Chibanda instead opted for an unconventional alternative. He recruited a volunteer force of grandmothers to staff the benches, and provided them with basic mental health training.

“One of the reasons grandmothers are so great for this is because they are rooted in their communities; they are considered custodians of local culture and wisdom, and they don’t leave their communities; they are so reliable,” said Chibanda.

He describes the training conducted for the Friendship Bench’s grandmother-led community health workers as rooted in evidence-based therapy, but also equally embracing indigenous concepts.

“I think that’s largely one of the reasons it’s been successful, because it’s really managed to bring together these different pieces using local knowledge and wisdom,” he said.

In 2016, after years of serving thousands of people in Zimbabwe, Chibanda along with academic colleagues from Zimbabwe and the United Kingdom tested the effectiveness of the mental health services provided by the Friendship Bench. The results of a randomized control trial were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association and overwhelmingly found that participants in the Friendship Bench project had fewer symptoms, and lower risk of symptoms of depression than control group participants.

“We were thrilled to bits with the results, which showed the intervention is having a big effect on people’s daily lives and ability to function,” said co-author of the study Dr. Victoria Simms, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

With the Friendship Bench model a demonstrated success, Chibanda and his methods have been an influential case study and inspiration to launching similar programs around the world including in Kenya, Zanzibar and New York city.

Accessible mental health care initiatives are needed more urgently than ever. According to the World Health Organization, in 2019, 970 million people globally were living with a mental disorder, with anxiety and depression being the most common. Global studies also found that the majority of those who need mental health care lack access to high-quality mental health services for a variety of reasons including a lack of financially affordable options, societal stigma around mental health disorders, and severe resource and funding shortages for medical practitioners.

In Zimbabwe, the Friendship Bench has been integrated into the national strategic plan for health, a testament to the tangible results and long lasting community impact it has yielded.

“This isn’t just a solution for low-income countries,” said Simms. “This may well be a solution that every country in the world could benefit from.”

SHOP THE CHANGEMAKER COLLECTION